Rivers of Relations

The Rivers of Relations Exhibit project was born through a tight knit community wanting to bring Indigenous issues in Binghamton, New York to the forefront of the conversation. Because the exhibit is now over, this corner of the internet is being used to document and preserve it for further educational purposes.

The exhibit focused on four major themes of Indigenous Binghamton and how they are all related: Native time, Native Politics, Native Kinship, and Native Ceremony. Each theme and its relationships will be explored across the entire exhibit.

The powerful Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy of the Five (later Six) Nations formed and provided a unifying form of government for the Nations in our region. The Haudenosaunee Onondaga, Oneida, and Tuscarora Nations, as well as the Delaware, were the primary sovereign nations in this region. The confluence region was home to a multitude of Indigenous agricultural communities for thousands of years.

Our exhibit team was primarily composed of Indigenous and non-Indigenous co-curators from diverse backgrounds.

Kaysha Nonowe Haile (Shinnecock, Thunderbird Clan) – Artistic Director – Kaysha is an amateur visual artist living in Binghamton. Kaysha uses art and design to frame her curiosities about the world and explore her heritage.

Shams Harper – Co-curator- Shams is a bicycle mechanic, farm worker, and activist living in so-called Binghamton, occupied Onondaga and Oneida territory.

Pauline Berkowitz – Co-curator/Research Coordinator - Pauline's love of agriculture, art, and community drives her activism in different local projects, such as this exhibit.

Chelsea Cleary – Assistant Art Director/ Media Consultant- Chelsea is a local artist, community organizer, and first time curator with deep roots to this Valley.

Dr. Katherine Seeber – Co-curator – Katie is an archaeologist and community organizer whose work is driven and informed by Indigenous women, communities, and perspectives.

Dr. Kate Ellenberger – Exhibit Design Consultant - Kate is a public archaeology specialist who assists heritage workers in communicating with the public.

Cara Burney – Technical Assistant - Cara is a local educator and community organizer.

Karahwino-Tina Square - Exhibit Opening Speaker Karahwino-Tina Square is Wolf Clan, Akwesasne Mohawk. She is an independent cultural educator who specializes in educating about Hotinonshonni culture, stories, history, and foods. She will be performing the Hotinonshonni creation story.

A view of three protest signs above a case of 1000 year old stone tools. A frame photograph of the Native Nations March in 2017 and a map of the traditional layout of a Mohawk Village frame this.

A view of a portraiture exhibit. Portraits of living and passed Indigenous New Yorkers from the Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, and Shinnecock nations are laid out atop a painted graphic of a river. Above is a traditional Haudenosaunee design in white and purple.

A Lavendar wall with a painting interpretation of Indigenous time. A large bald eagle sets atop a swirling timeline sprouting from the back of a turtle.

Dr. Seeber introduces Mohawk Wolf Clan storyteller Karahwino-Tina Square at the exhibit opening.

Karahwino-Tina Square, Wolf Clan Mohawk Story teller shares part of the Thanksgiving Day address in first Mohawk then English at the Exhibit opening

a crowd of people standing in front of the portrait exhibit opening night of the Rivers of Relations Exhibit

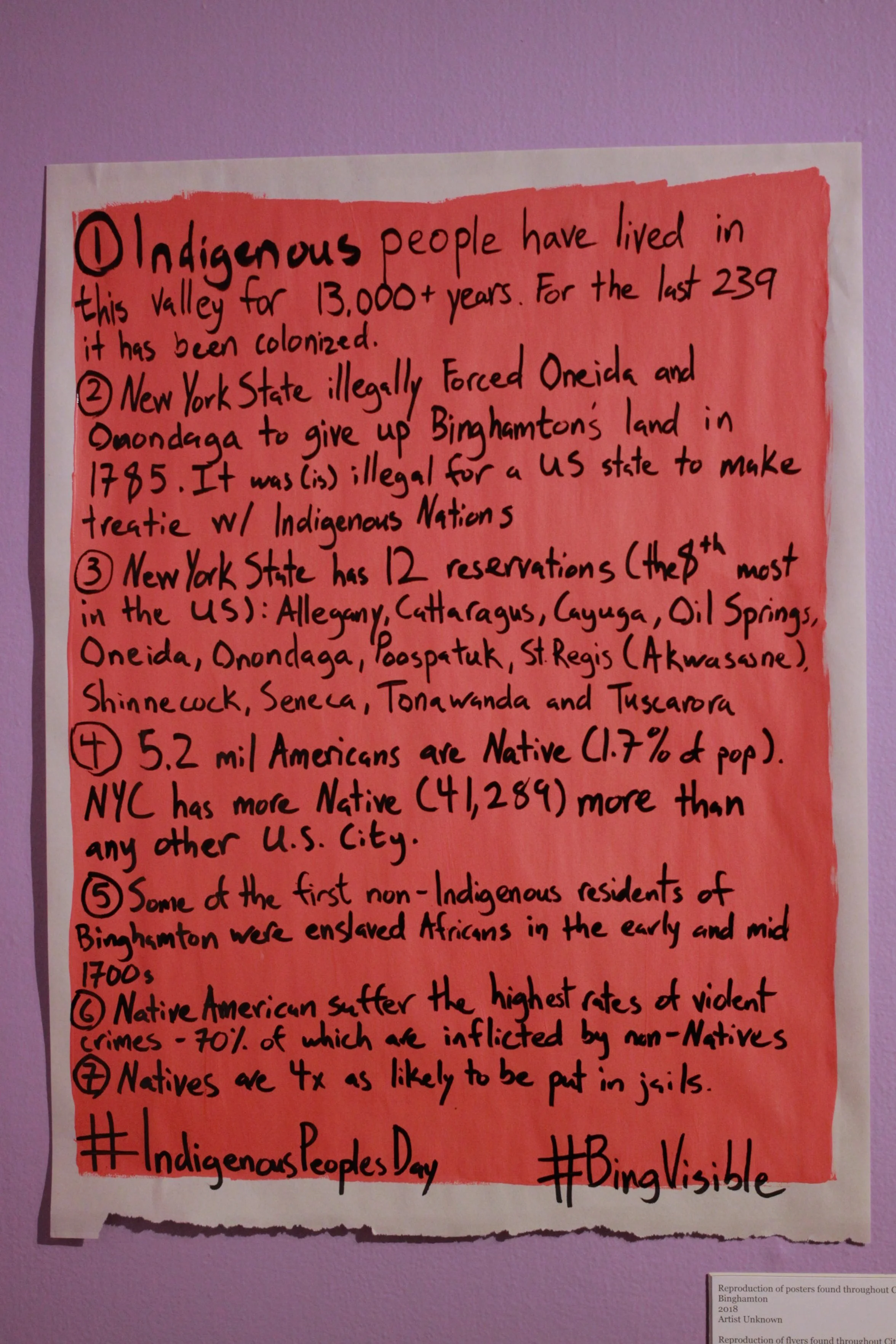

A mother and daughter stopping to read the protest signs on display at the Rivers of Relations exhibit. The protest signs are a bright coral with black lettering, listing of 10 facts about Native people in America

Columbus Day Protest Sign with 7 facts 1) Indigenous people have lived in this valley for 13000 years. For the last 239 it has been colonized. 2) NY State illegally forced Onedia and Onondaga to give up Binghamton's land. 3) NY State has 12 reservations: Allegany, Cattaragus, Cayuga, Oil Springs, Oneida, Onondaga, Poospatuk, St. Regis (Akwasasne), Shinnecock, Seneca, Tonawanda, Tuscarora.

View of the exhibit featuring politcal cartoons, zines, and treaties.

Exhibit visitors looks at the river of related portraits

Stone Square Grinding Tool from an archaeological site in the Chenango Valley. It was used to shape pottery.

Relations of Time, Politics, Ceremony, and Kin

Indigenous people have always existed in this valley, which now contains the city of Binghamton, New York where this exhibit stands. For ten thousand years Native people have interacted with this land and experienced it in ways that may seem foreign to those used to the western, Euro-American ways of experiencing the world. Western worlds are compartmentalized, classified, and boxed in, and people are defined by how they classify and box themselves. Indigenous worlds are defined by how each person is related to the worlds and beings around them.

Indigenous traditions teach seeing the world through their communities’ ways of knowing. This exhibit seeks to illustrate that experience through the eyes of Indigenous guest curators and their allies. The Indigenous world is a world of relations, an interconnected web of relationships between people, other beings, places and elements.

Our Presentation of Time

Time frames all aspects of life. We have chosen to begin with time, because to grapple with the differences in western perspectives and Indigenous perspectives, one first has to understand how Native Americans understand where they are in the world.

Indigenous time is not linear. The different communities of Natives who lived here have typically conceived time as a cyclical, seasonal continuation, like a spiral. This is an essential and fundamental aspect of many Indigenous consciousness. When all aspects of life circle back onto themselves, the layers of relationships between things define how we understand the world and our place in it.

Native Americans have been in this area for at least ten thousand years and we will be here thousands years from now. Each moment is part of a cycle that has happened before and will happen again. Each season is part of the same season that happened before. As can be seen in the time spiral to the left, all parts of time are related and overlapping.

Our Presentation of Politics

Indigenous politics are not confined to one area of life. Political issues are related with all other parts of Native life. Native communities are typically organized according to kinship clans, within tribal Nations. Indigenous communities have always been negotiating social and political worlds, long before colonization. The League of the Haudenosaunee was the major political group in New York both before European contact and afterwards. The League consists of the Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Mohawk, and after European contact, the Tuscarora as well. They make up the oldest democracy in the Americas. In many ways, the League of the Haudenosaunee is an egalitarian political system; it uses consensus as a method of decision-making.

The pipe bowl and beads in this display are objects that are part of the Haudenosaunee political system. Smoking tobacco plays a big role in relations between people, both in formal political interactions and in everyday life. Wampum beads like these have been traditionally used in negotiation and testimony for many northeastern Indigenous Nations. The projectile points were used for everyday activities, but in modern times, versions of these are often used by non-Native people in art and logos, and objects like these are often unearthed and collected by non-Native people who consider it a hobby.

Contemporarily, politics are part of the everyday life of colonized communities. As you can see from the legal documents surrounding you in this room, many Native Nations in New York state are constantly negotiating and interacting with the government built by colonizers to maintain their traditional relations. Many Native communities have become displaced or restricted.

Our Presentation of Kinship

Indigenous kinships, or relations, go beyond the nuclear families that most western people think about. These connections extend to people who share the same clan, to particular aspects of the natural environment, to homelands, to sacred places, to sacred animals, and to people and beings who share relations with our ancestors. These are our kin. Kinship also defines the correct way to live in the world.

As explained by Deborah Doxtator, the English term “clan” is an incomplete translation. “The word otara in Mohawk, means land, clay, or earth as well as clan. When you ask who is your clan, you ask ‘what is the outline or contour of your clay? This refers to the land you can access and the territory to which you belong… Land relationships are the basis of understanding clans and political structures.”

On this wall you see portraits of Indigenous people whose traditional territory was or is in this area, or close to it. Good Peter was an Oneida chief in Oquaga (modern day Windsor NY) in the mid 18th century who was very important during the French and Indian war. Joseph Brant was a Mohawk war chief who married an Oquagan woman and often lived at Oquaga as well. He later became famous for his role in the American Revolutionary War.

Our Presentation of Ceremony

Jobs such as basket weaving, tapping Maple trees for syrup, canoeing along these rivers, planting crops, gathering or hunting for food, making tools out of stone, making cooking pots out of clay, were all daily tasks for the Indigenous communities who lived here. Many of these are still practiced by us today.

But these daily chores were also spiritually infused tasks that helped people maintain their spiritual connections to their ancestors, spirit beings, plants, animals, and the earth. By accomplishing these tasks, Native people have maintained their bodily and spiritual nourishment.

It is important to understand that the significance of relations for Indigenous people goes beyond stereotypical portrayals of Native Americans being “one with the earth”. Relations are deeply felt but they are also structured by culturally specific rules and histories in each tribal community. The direct care and manipulation of these valleys helped shape the earth here to allow these communities to thrive both bodily and spiritually.